A turning point

As the day for my Fulbright trip overseas nears, I recall my first trip to Ukraine, my parents' homeland, in the spring of 1991. This trip opened my eyes and soul to a long-suffering yet hopeful people, to a land beautiful but ravaged by the Soviet system, and a culture rich but sabotaged. As I experienced the compelling visitation of Ukraine's weighty history (including the little-known 1932-33 Holodomor under Stalin's reign of terror), I vowed to bear witness to such tragic events. It was a turning point in my creative work and world view.

Subsequent trips to Ukraine followed and each influenced me and launched a more visceral creative approach to content and media. Two years after the Soviet Union unravelled and Ukraine became an independent, sovereign country, I travelled through the part of the country that was once Scythia, and toured historic archeological sites. This deepened my understanding of Ukraine's ancient cultural heritage, now being reclaimed.

Ten years after the nuclear explosion in Chornobyl, Ukraine, I visited the Zone, ground zero. I was left with a lasting impression of nature's power of reclamation and healing, even in the face of deception, destruction and loss. I saw nature growing over abandoned buildings and grounds, resolutely regenerating life, spreading her mantle over the dust and decay, and creating anew. Since then, curtains of trees, tangles of branches, vines and thorns, have become recurring motifs in my work, concealing and revealing a text-laden ground.

My work begins with collecting print news accounts about specific meaningful historic and current events which I want to explore in more depth. I arrange them in a sort of self-perpetuating dialogue, then collage them onto canvas or paper. The collage becomes the ground for imagery that evolves by adding and subtracting elements through painting, drawing, and various mark-making with oil paint, charcoal, chalks and wax. At the same time, I examine the nature of print media, how information is disseminated, what is revealed and what is concealed. I see how narratives can be created, implied, hidden, disguised. My ongoing process of layering and abrading words and images reflects my deep interest in how we come to know history—how experiences submerge, resurface, and unravel over time.

These artworks and commentaries are examples of my current work.

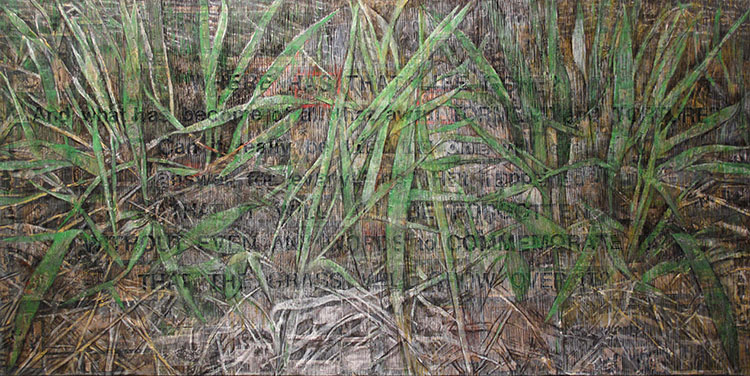

This is an elegy for all the victims of the 1932-33 Holodomor genocide, an artificial famine orchestrated by Stalin. Seven to ten million Ukrainians died of starvation, specifically targeted by Stalin, who wanted to deal a "crushing blow" to the backbone of Ukraine and her rural population.

In this work, a ground saturated with text and images of the Holodomor is overgrown with blades of grass and shielded with the words of writer Vassily Grossman, a Holodomor witness. He asks: "Can it really be that no one will ever answer for everything that has happened? That all will be forgotten? That the grass will grow over it?"

Denial of the Holodomor by Soviet authorities was echoed at the time by many prominent Western journalists, like Walter Duranty of the New York Times. The Soviet Union adamantly refused any outside assistance because the regime officially denied that there was any famine. There was much disinformation, lies and propaganda, and, like today, few journalists reported the truth of this genocide. Among those who did report the Holodomor were Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones. A 2019 film by Agnieszka Holland, Mr. Jones, addresses the coverups.

The Maidan Revolution of Ukraine began in the winter of 2014 as a peaceful student grassroots protest. But when the president of Ukraine broke his promise to sign an association agreement with the EU, turning to Russia instead then fleeing there, the protests grew, erupting into violent clashes between protesters and riot police, and became a de-facto revolution. Over a hundred people died at the hands of brutal police. The victims were duly mourned, honored and buried, while the killer cowards fled.

In this painting, seemingly opposing elements inhabit the scene—the blazing fires amidst the layers of ice. But the paradox sets the stage for cathartic action. Through the haze and smoke of scorched land and melting snow, the Ukrainian nation sees redemption and resolution.

In 2014, in quick succession, as if releasing pain and anger, the people overthrew their corrupt president, held free elections, and chose a new president who restored the country's constitution, advancing democracy and rule of law. From afar, the West simply saw an oppression-free landscape, but up close one could discern words and imagery that carried another message of a destabilizing, aggressive Russia on the rise. It led to today's horrific war and Ukraine fighting for self-determination once again.

As soon as the 2014 Olympic Games ended in Russia, Putin put his land-grab plan into action and annexed Crimea, at the same time moving Russian troops to the Eastern Ukrainian border and then across the border in an invasion of Ukraine. Europe and the West undertook virtually no action to prevent these events and protect Ukraine's territorial integrity and sovereignty. In 1931, at the time of the Stalin-orchestrated famine-genocide in Ukraine, the Ukrainian poet Oleksandr Oles wrote his poem "Remembrance," lamenting the deaths in Ukraine and pleading for help. I copied his poem onto the surface of accrued collaged reports of the latest Russian aggressions. Each stanza ends with the refrain "and Europe was silent," mournfully echoing Ukraine's plight.

This monumental neckpiece is based on a 4th-century ancient gold pectoral that was excavated in 1971 from a burial ground in southern Ukraine. The prized artefact bears witness to the productive co-existence of the Greeks and the Scythians, their trade and exchanges at the time. The three-tiered gold pectoral first shows the domestication of animals, then the lyrical intertwining of fauna and flora, and, at the bottom, warring mythical griffins, hunting prey and guarding their priceless possessions. Metaphorically it characterizes Ukraine. I've updated some of the figuration. The ground is made up of collaged news accounts of Ukraine's early years of independence since the 1991 demise of the Soviet Union, and her continuing struggle with Russia's constant interference and invasions. The collaged ground is shrouded in a dark haze, and the words of Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko hover over it. The bard calls for Ukraine to keep fighting for freedom, truth, and justice and "you shall overcome." Some of the text and images of recent political figures and events invade the body of the choker itself, which as a neckpiece is meant to embellish but can also constrict and choke. Whether enhancing or choking, either way, the past informs the present.

Houston-based artist Lydia Bodnar-Balahutrak received a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award for the academic year 2022-23. Her Fulbright research project is a collaborative study of socially and politically informed art created by contemporary Ukrainian artists. The project was designated for Ukraine, but due to the war in Ukraine, it was re-assigned to Poland. She will be able to travel and engage directly with refugee artists displaced from Ukraine, and to connect virtually with artists and institutions inside Ukraine.