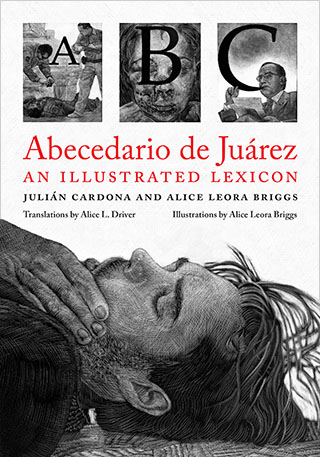

Abecedario de Juárez

I was educated early in the fragility of life. When I was seven years old, the Tetons hurled my oldest brother into an abyss. Our neighbors fared worse. The father and son went fishing on a river that pulled them out of this world. Six months later, an experimental reactor exploded at the National Reactor Testing Station where my father worked. Three young men died. Whatever was left of them was sealed in lead coffins and shipped to faraway cemeteries. Our family had no words. We fell silent about these deaths for nearly six decades. It's been fifteen years since I first walked into Ciudad Juárez. Long before then, I forgave my desire to comprehend and speak about la frontera, an extreme of understanding.

By many accounts—no one can know the exact numbers—there were over 3,000 homicides in Juárez in 2010. That same year, my friend Julián Cardona and I set out on separate paths to respond to this plague of deaths. We talked regularly about our respective projects and routinely met in Juárez and on Skype. It became important to look into one another's eyes as we wrote and spoke. As our exchange of words and images gathered speed and intensity we realized that we were working toward a mutual goal. By 2015 we'd made a career of sweating, laughing, and handwringing, without benefit of knowing where our toils might lead. By 2018 we had to set an alarm to remember to get up and walk around every 30 minutes, otherwise we would work until cemented to our chairs. Computers grew feeble during this decade, some were repaired, and one was silenced forever by a strong cup of coffee. Our task was equal parts exhilaration and exhaustion, and in the end, terribly painful. In September 2020 when our book, Abecedario de Juárez: An Illustrated Lexicon, was accepted for publication by the University of Texas Press, we met on Skype to toast each other. As he lifted his beer to take a sip, Julián turned his phone's camera to the Juárez sky. Several days later he looked into the same sky as he lay in a street of the city he loved and loathed. Julián Cardona died on September 21, 2020, just outside of his favorite coffee shop.

Our illustrated glossary is a mine field of Juárez slang used by criminals, pundits, government officials and other Juarenses who struggled to find words. It explodes into first-hand accounts of extortion, kidnapping, torture and murder, provided by victims, witnesses, perpetrators and media accounts. It is a window that faces the consequences of sexenio de la muerte, six years of death (2006-2012), otherwise known as the administration of an ex-president of Mexico, Felipe Calderón.

Here are a few selections from the images, slang and narratives in Abecedario de Juárez.

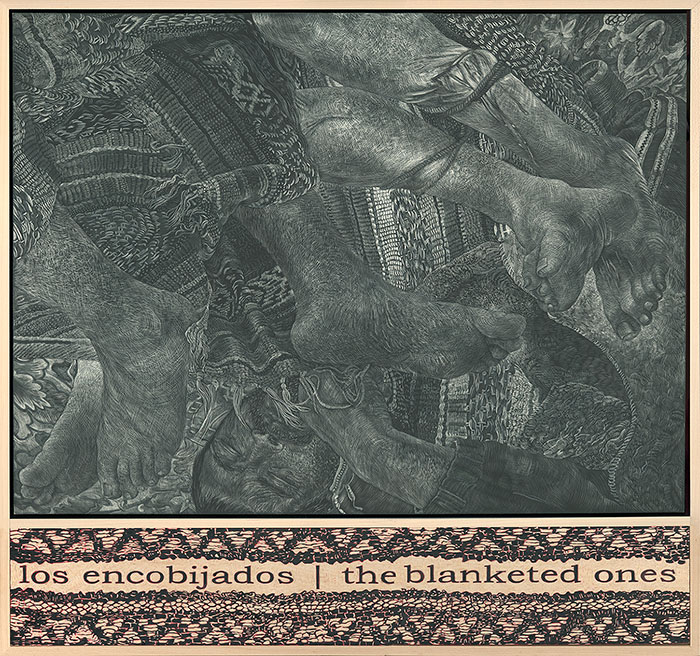

Encobijado/encobijar: a murder victim whose body is rolled in blankets and dumped in Juárez or the desert outskirts of the city/to roll a corpse in blankets and dump it. Some Juarenses believe that encobijados are tortured by police in motel rooms. When they do not survive the ordeal, they are wrapped in blankets to avoid soiling official cars. Literal meaning: blanketed one/to be blanketed. Related terms: crimen uniformado, entamalado

No enrranflados: those who answer to no one; a ranfla is used to describe a car, a smooth ride. No enrranflados are not members of a gang or "family"; individuals who do not work for or report to the police or military; those who operate without the protection that affiliation provides. Literal meaning: those without a ride. Related terms: ¿con quién estás puesto?, familia, la lista, Los Mansos, La Placa

Behind bars a teen named Toby attempts a complete overhaul. He looks harmless with his neat haircut, his slight frame, his skin unmarked by scars or tattoos. In a blue T-shirt, khaki shorts, and sneakers, he is one of over 3,330 minors arrested in 2010 for robbery, kidnapping, homicide, and other crimes.

Although he is legally a child, Toby is also the father of an infant, now six months old. He regrets his mistakes and wants to raise and educate his son to avoid them. In jail he works as a gardener, sings in the choir, plays the piano and guitar, and attends religious services. His wife, mother, and older sister visit him.

If he could talk with his friend, a malandro who introduced him to robbery, Toby thinks they could work together to make amends for their terrible decisions. His mother informs him that this is not an option. His friend is dead.

Luis Javier Martínez, founder of Auto Value, a chain of auto parts stores, was nearly extorted out of existence:

[He] understands that criminals and the municipal police work side by side to divvy up the city and even use the same accounting system. He compares his experience to that of a man with a large dog on a leash. "Suddenly you don't know who is following who. Is the owner walking the dog, or is the dog walking the owner?"

According to witnesses, four men attacked Captain Herrera González. Reports from state authorities note that eighty-three shots from an AK-47 and an AR-15 hit him in the neck, chest, abdomen, arms, and legs. He had just finished his shift as night manager in the Central District of the municipal police and was on his way home.

At the close of 2008 there are 1,623 homicides, and 95,000 cartridges are collected at crime scenes, an average of 58.5 per victim. Herrera González's execution warranted an additional 24.5 rounds. Ciudad Juárez becomes the murder capital of the world.

Alice Leora Briggs was born in an oil boomtown in West Texas, grew up in Idaho's Snake River Valley, and woke up later on la frontera, the borderlands of the United States and México. Her investigations into human frailties have generated thousands of drawings, woodcuts, letterpress books, broadsides, and site-specific architectural installations, as well as several books. Her artworks have been featured in over forty solo exhibitions and are included in over thirty-five public collections, including Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Library of Congress, University of Oxford's Bodleian Library, and Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Publications include Dreamland: The Way Out of Juárez (University of Texas Pres 2010), an illuminated manuscript-police blotter with writer Charles Bowden, The Room (printed at Flatbed Press, Austin, 2016), a suite of twelve chine collé woodcuts with poet Mark Strand, and Abecedario de Juárez: An Illustrated Lexicon (University of Texas Press 2022), in collaboration with photojournalist Julián Cardona. Briggs served as a Fulbright Scholar at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, Slovak Republic and is a 2020 Guggenheim Fellow. She now lives with her husband and 100-year-old mother in Tucson.