Telescope

In 2002 I took a trip to China with my parents and extended family to see where my mom was born and to tour that mysterious country that was part of my mother's past. My grandparents were medical missionaries in Shandong Province. I grew up in Dallas eating Chinese foods, hearing stories from my aunt and mom of playing games with their Chinese girlfriends, warlords fighting, bullets whizzing through the air, Japanese invading, and the 100s of poor people my grandfather sacrificed his life to help. I had a general love for China but during our tour something happened inside me that I could not explain, it felt as huge as the country itself. At one point as we were walking along I turned to my mom and said, "I feel like I was born here, I don't want to go back to the US." Over the next several years and two subsequent curatorial trips to China I moved to Beijing in 2008. To many friends it was a totally irrational move. I had a great position as the founder and curator of the Hammer Projects at the Hammer Museum, LA, and was able to give many emerging artists their first museum shows. It was immensely rewarding to me but after 10 years as the curator of the Drawing Center in NY and almost 10 years at the Hammer Museum I was beginning to become restless, the artist in me wanted out. I became so insanely passionate about going and starting over at the bottom again in a new and unknown place that nothing was an obstacle to realizing this new found dream. It was time for change so I left the museum and landed halfway across the world in a country and art world I knew very little about, had no close friends, only a few acquaintances, but it was, in a strange way, home.

In 2008 everything in China was emerging and expanding, including the number of artists and galleries. With the opening up of China, the sudden economic boom, and softening of many regulations It was possible to become a contemporary artist that was never an option before. I was told, at a later date, that the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing was now receiving one million applications for admittance a year. The artists I met were making work with an urgency, like it was vital for their survival. It wasn't all good, but it was electric and challenging. The art world seemed to be one big family finally coming together under one flag of hope. For many years artists had been denied access to the outside world, their voices and identities silenced, and now that there was a crack in the wall they anxiously embraced the potential freedom to be a part of it all. The energy at that time was palpable and everywhere. It reminded me of the East Village in NY in the 1980s where the sky was the limit and anything could happen. It also recalled the climate in LA in 1999 when I left NY to join the Hammer Museum. The city was in an exciting cultural shift and on the cusp of challenging NY for its place of importance in the US art world. So, again, I wanted to go to a new uncharted world and be a part of it too. To be honest, I felt that the energy, purpose, and desperation in China was missing in the US where life was so much more comfortable and easy. It is a desirable lifestyle but, in time, has a deadening effect on the depth and quality of art. In the US everyone was free to say and do what they wanted but it was not treasured but taken for granted. In the end art was becoming too self referential and the only thing to fight for was a gallery show and a review. I wanted to feel the grit and uncertainty of life again in a new emerging culture and help these invisible artists break out.

As I was considering the many reasons why I wanted to go an image came to mind, it was of a cultural bridge between our countries. I believed that I could do that. How? Just pull from my museum and artist experience, start small, and build. Over the ensuing years I curated several Chinese exhibitions for the Hammer Museum, exhibitions for LA, Chicago, and NY galleries, the Asia Society, and CAM Houston giving many Chinese their first exposure in the US and giving the local art world a glimpse of art that they could never have seen otherwise. In April of 2011 Holland Cotter wrote a review in the New York Times of an exhibition I curated at Meulensteen (Max Protetch Gallery) in NY, called In A Perfect World . . ., and ended the article with this: "New York rarely sees this much new art from China in one place, and as a city with lingering ambition as an international art center it needs to."

As I became more and more familiar with my Chinese surroundings I felt I needed to make another move, the one I came to China for but didn't know it until then. In 2012 I opened a nonprofit type of space in Beijing to be able to work locally with the artists. At that time, to my knowledge and memory, there were no (or just one) nonprofit type spaces in Beijing. There was no philanthropy, no funding, no 501c3s, no support foundations, and no understanding of what a nonprofit or alternative space was. There was definitely a need to introduce this into the art system as it started its move into focusing on sales and auctions to determine the value of the artist and art. I rented an old massage parlor that was going out of business in Cao Chang Di, an urban village adjacent to the government sanctioned and much more expensive 798 art district, and opened Telescope. Several Chinese and international commercial galleries had opened high end galleries in the area so I was not stranded alone trying to make my way. It was a real urban village with narrow streets that a car could barely navigate. Dogs and children ran about, some people cooked their meals in woks outside of their buildings, older men and women sat in broken sofas loudly chatting the day away, there were restaurants, hair solons, markets, one after another, elbow to elbow, it was a taste of an older China that was rapidly disappearing in the rush to modernization. I was in heaven.

I invited an artist, whose studio I had twice visited, to have an exhibition at Telescope but he refused despite the fact that he had no gallery representation and no one showing his work. He later agreed and told me that he first hesitated because he didn't really know who I was, what I was doing, or what a nonprofit space was. After his exhibition he told me that the experience was the most important one of his life and that his work "belongs in the nonprofit context." Now we are best friends. "Another artist I showed told me that artist friends of his had cautioned him not to show with me because I would "steal his money." The fact is that I was paying for everything out of my own pocket, without any funding. I did this for reasons they did not understand at the time. Through the grapevine I also heard that many people thought I was a fool because I was not making any money by running a "nonprofit" art space. It seemed really stupid to them. But they had no idea what the possibilities of the bigger picture of what I envisioned were. Today people I know and people I have never met before come up to me constantly telling how important Telescope is and how it has impacted their lives and the art community, and how encouraging it was to them. as students at the art academy, giving them hope for the future. For the past ten years or so, there has been a surge of artist run spaces, not for profit style galleries, and independent projects all over Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and China.

In 2020 I was forced to close Telescope because of regulations stemming from Covid and the lockdown. In fact, the Cao Chang Di district built a blue metal wall set in concrete around the entire area with two guard posts, shutting it off from the outside world. Only people who lived there could go in and out, and even they were regulated. I was not allowed back in and had to give up my lease. During that time Telescope morphed into a space without (blue) walls as I have continued to work with artists and curate exhibitions in Beijing and the US.

Most recently I've been working on a group exhibition of seven artists for a new Beijing gallery, Click Ten, entitled Shadow of Things, which opens in October 2024. The exhibition title, Shadow of Things, can be interpreted and viewed in several different directions. It's not based in a philosophical, historical, or psychological idea that requires selected artists' works to support a curatorial premise, but is a poetic phrase that came to mind one morning like a cloud passing by my window. Although it is complex in that it suggests many avenues of thought, it is more simply about relationships; relationships between things seen and things unseen, the mutable and the immutable, body and spirit, form and meaning. What relationally happens to an individual artwork when placed in a group of other artist's works in a shared neutral space? And what is the relationship between curator and artist?

Relationships are the heart and soul of curating for me. I see things online; for sure, it's a fantastic resource, but I don't scour the internet with the express purpose of filling holes for an exhibition with stuff I have never seen firsthand. I am not just looking just for an object to hang on a wall but for a life to interact with. The building of relationships with artists is an important part of curating. It provides an in-between space to build trust and friendship, mentor, teach, help artists go higher and deeper in their lives and work, and equally learn from them. To me this is part of what curating is, and you could even say it is a responsibility.

I am an artist and was an artist long before I became a curator. The reason I left Texas and moved to San Francisco after graduating from the art department at North Texas State University (UNT) and then three years later moved to NYC was solely to be an artist. Curating happened by surprise while I was working at the Drawing Center in 1990 when a new director was appointed, Annie Philbin. One day she walked up to me and told me she was appointing me curator. I was totally surprised and told her that I was not a curator and didn't know how, and she told me that she had never been a director before and didn't know how either. So, we both laughed and learned together on the run. We had several important things in common; passion, a love of the artists, creativity to think outside of the norm, and a vision on what the Drawing Center could be, and what the emerging artists needed. When I accepted her invitation I made a silent vow that if I ever stopped making art then I would quit curating. Something inside me knew that my ability to curate and succeed depended on my being an artist. I have never broken that vow and now, even though I am still curating and always will, I am focusing more and more on my own work as an artist.

If anyone reading this has any aspirations of becoming a curator, you do not necessarily need a degree from a prestigious curatorial studies program. You just need to find a cheap storefront space in a edgy part of town, a garage, or your apartment, or even a parking lot at an abandoned building site for a one day show. One key is to stay within a simple budget that you or a team can afford. Going into debt doesn't help anyone. Longevity is important. DIY is cool. How do you find artists? Go to gallery openings, meet people, share your vision, visit emerging artists' studios and their friends' studios, see what is going on in the art community. Then, invite some artists to have a show. Most emerging artists will jump at the opportunity. Or invite an artist to curate a show at your space. I remember when I first rented an old run down massage parlor in Beijing for my new gallery, I did nothing with it for months and months waiting for promised financial support that never came. I was afraid to step out, afraid of failure, but one day I thought, I'm not going to wait any longer, I can do this myself, and took the leap. Within a month and half I opened Telescope with my first of many exhibitions.

Shadow of Things

Shadow of Things runs October 13 to December 15, 2024 at Click Ten Gallery in Beijing, curated by James Elaine and featuring work by artists Dan'er, Edie Xu, Liu Dongxu, Robbin Heyker, Stephen Gleadow, Xie Hongdong, and Ye Su.

The exhibition title, Shadow of Things, can be interpreted and viewed in several different directions. It is not based in a philosophical, historical, or psychological idea that requires selected artists' works to support a curatorial premise; but it is a poetic phrase that came to mind one morning like a cloud passing by my window. Although it is complex in that it suggests many avenues of thought, it is more simply about relationships; relationships between things seen and things unseen, the mutable and the immutable, body and spirit, form and meaning. What relationally happens to an individual artwork when placed in a group of other artists' works in a shared neutral space? And what is the relationship between the curator and artist?

Oftentimes shadows are seen as darkness, the dream world, or the presence of evil, but they are also a place of refuge from the heat in the cool of the shade. They are like sketches or outlines of things seen, or they prophesy as harbingers of unseen things to come. One biblical account tells about an apostle whose shadow healed the sick people lying on the side of the road as he passed by. In the case of this exhibition this would illustrate the power of the artist's creative spirit radiating outward into the world through their work. Ancient cultures developed devices for telling time and seasons called sundials or shadow clocks. They were instruments to show the time of day or seasons of the year by the shadow of an object cast by the sun on a cylindrical surface. These are but a few of the many references to shadows found in diverse cultures throughout time. They could be real or metaphorical links to the installation design of works in the gallery space or to the individual works themselves.

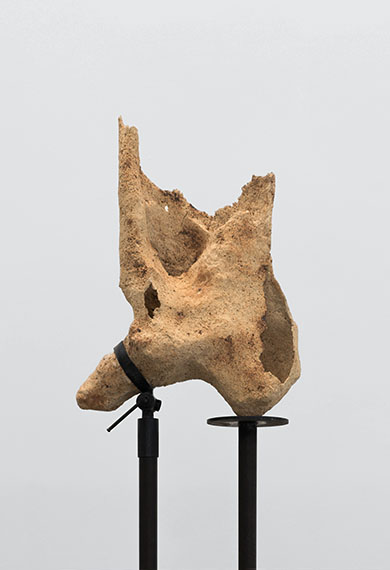

What is a "thing"? It is a really useful word that describes something or anything that can't readily be described for one reason or another. Art constantly presents to the public the question of "what is it?" It is not always necessary to know what some works of art might be or mean, but just to allow oneself to ponder and enjoy or be challenged by them for what you see is enough. As a noun, the word "thing" normally would refer to three dimensional or sculptural objects. But even two dimensional paintings and photographs depict and record three dimensional things. The Dhana series of photos of Xie Hongdong and the clay sculptures of Edie Xu are both steeped in a grey relationship of shadow and thing. We can partially recognize them but not define them completely. Xie's Dhana series resemble spirits or shadows drifting out of Xu's ancient bone-like archeological discoveries.

Robbin Heyker's and Stephen Gleadow's long years living in the old Hutongs and outer rings of Beijing provided them an endless source of still life mysteries and discarded materials for their paintings and sculptures; such as cardboard or pieces of wood leaning against the exposed tires of vehicles parked on the narrow streets, boarded up broken windows covered in years of colored plastic bags, duct tape, slats and nails, a slap of paint on the side of a building to cover up previous markings, discarded stools, torn banners, books, and papers. Their works in their own unique ways illustrate or shadow the immediate day to day culture around them. Ye Su's ink paintings are narratives culled from his dream life. They are like individual frames of a surrealist film and are flooded with strange people, places, shadows, and things surreal and things known. There are 18 individual paintings in his Tannu Uriankhai series but are installed as one massive tableau, one life long narrative in one second.

Liu Dongxu and Dan'er both borrow from specific and diverse cultures reinterpreting their common household, commercial, and industrial objects into minimalist sculptural forms. Liu appropriates objects and brings them out from their original context while Dan'er actually goes into different cultural environments to absorb and create from within.

One important element I have not mentioned directly is "light." Shadows cannot be seen without light, light of the sun or artificial light of a gallery. Light always represents truth and truth reveals all things hidden. It exposes details and motives, beauty and ugliness, and even has the power to cast the shadows from our sight.

Artist Introductions

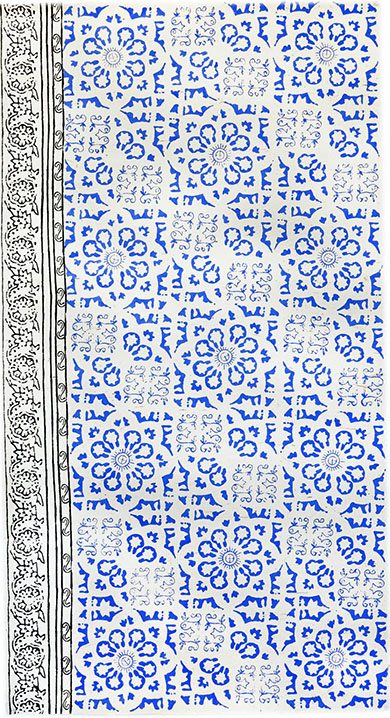

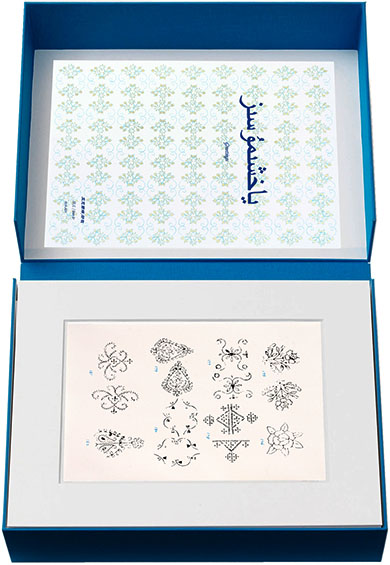

Over the years and through her travels to several western Asian regions, Dan'er has collected more than 400 stamping blocks of differing sizes and shapes. These wooden stamps are carved with intricate geometric and natural plant patterns for stamping, or printing, on textiles and paper. They are decorative but carry deep cultural significance for each region they come from. During her time on the road she met many folk craftsmen who taught her how to make her own brushes and compose imagery and color work with a new improvisational freedom that she was not used to seeing in trained classical painting. The stamps are more than just another artist's tool for making work, they have become keys that can open doors to a deeper understanding of the creative spirit and process of making art as she learns the ways of local artisans. Dan'er cross pollinates language, aesthetics, and motives of different cultures through her interaction with real people and the transferral of visual folk elements and materials into her work.

From clothing to sculpture, fabrics to ceramics, from the mutable to the immutable and spirit to flesh, Edie Xu's work spans multiple mediums and cuts like a surgeon's knife exploring the body, separating shadow from thing in search of the substance and meaning of existence. Although Xu studied fashion design at the Art Institute of Chicago, her creations were but a breath away from sculpture. For Xu, clay is like fabric or flesh but also like bone that gives shape to the flesh: consider Lee Bontecou's strange canvas and wire constructions and Henry Moore's bronze reclining figures. Xu bridges those two by turning the body inside out where bone becomes fluid and takes shape as flesh exposing the fragility of the internal self and the mental and physical struggles of the mind and body as they move through time and space.

Liu Dongxu appropriates the language of architecture and commercial industrial design to reinterpret nondescript and familiar objects through the perspective of minimalist sculpture. His materials are common things from our environment that, perhaps because of familiarity, have become invisible to us, such as the ubiquitous products discovered shopping online, fruit and vegetables at outdoor markets, electronic hardware, and countless ordinary things found in our homes and businesses. Through removing, deconstructing, splicing, reordering, and replicating these materials, Liu transforms them with diverse materials giving them new identities. By transferring his finished objects to a new contextual environment, they perform a new function as art. Nevertheless, the shadow of familiarity of their previous lives in our memory and emotions remains.

At the first glance and the first time one sees a Robbin Heyker painting it's easy to think of it as purely random, simplistic, and that you immediately "get it." This is one of the tricks of his work. As a young man he wanted to become a magician and taught himself many magic tricks. Robbin states, "At a certain point you master a trick and magic is created before your very eyes, although you know perfectly well it's a trick." Sleight of hand, or manual dexterity (skillful deception), is how a magician fools his audience. Heyker never tries to fool anyone, but the skill in which he selects and juxtaposes his elements and the way he paints disguises the depth and sophistication of the painting. His elements are hidden in plain sight though; the scale of the canvas, size and number of images, juxtapositions, colors, relationships, shapes, edges, translucency and opacity of paint, etc. They remind me of an Alexander Calder mobile where everything is perfectly balanced and light as air. Under it all, Heyker's paintings are actually methodical and complex, but at some point in viewing them they gain a calm and poetic resolution whether one understands them or not.

Stephen Gleadow has created a detritus refuge archive from his foraging excursions into abandoned buildings, razed communities, and construction fields in Beijing. The 2010s were a rich, fertile and ever-shifting time. Heiqiao was in curious bloom and the sky was the limit. That landscape and history had a direct and vital impact on his paintings and sculptures. In his subsequent post pandemic works Gleadow has taken a more internal studio focus using "leftovers from that time." Materials that have resurfaced from his collections are pages from out-of-date encyclopedias, discarded books, dictionaries, blueprints, and his older drawings that he glues to canvas. They become the starting points for his new paintings. He also cuts and paints random shapes from these materials that correspond to his interest in astronomy, star maps, radiographs, information graphics, etc, then adheres them to the canvas in layers on a grid system. In between layers he sands the surface erasing and creating more imagery and then repeats this process as many times as needed. The results are a kind of archeological space voyage abstraction, or a fossiliferous limestone foundation for the building of a new city.

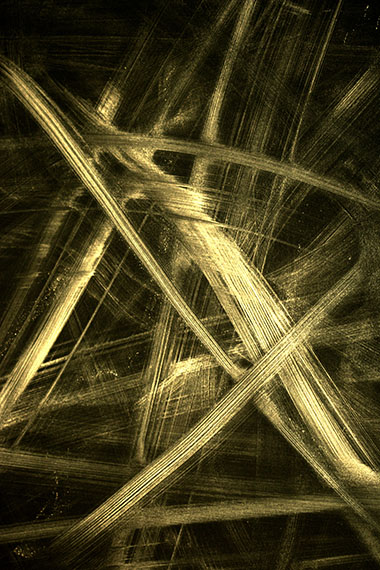

Xie Hongdong peers into the microcosmic landscapes of familiar territories yet undetected by the naked eye. His photos evoke the feelings one might have if looking through a glass floor of a ship at sea or through a glass ceiling of a satellite in space. New worlds and possibilities appear, endless in hope and wonder in their sometimes heart-stopping mystery. Xie's photographic investigations into the natural world around him are not fabricated or computerized, they are real. He sheds light in the darkness and reveals what we cannot readily see. His process of searching, finding, and creating is largely intuitive, poetic, and a form of self reflection and contemplation on his own existence. Like taking a walk through the subconscious, his process takes time, sensitivity, and perseverance. "The experiences of life can be quite fragmented, colliding, separating, but eventually they reunite like the veins of a leaf at the stem," states Xie. This is the heart of his work. We travel far and wide through time and space, get lost at times, but the act of creating is the tie that binds Xie to nature, home, and to himself.

"The dream world is another kind of reality," states Ye Su. For more than ten years he has been continuously writing about and transcribing his dreams into his paintings, drawings, and different types of projects. In an attempt to break through the flatness of paint on canvas to better represent the multi-dimensional quality of dreams, Ye Su chose to change and simplify his materials. In the Tannu Uriankhai series he uses only traditional Chinese ink on rice paper and alters the format of the page to a 3:5 aspect ratio. This gives the horizontal work a widescreen cinematic feel, while the vertical works refer to the screen of a smart phone. Ye Su's black and white palette separates the imagery from the color of the natural world keeping it in the realm of the memory and the dream state. Tannu Uriankhai is an area located in north western China. Towards the end of the Qing Dynasty, Russia gradually gained control of it. Now, the name Tannu Uriahnkhai has become only a symbol with no specific reference. Its history has been forgotten or erased like the ephemerality of a dream.

James Elaine is an artist and curator who lives and works in Celeste, Texas, and Beijing, China.