The Mountains Are In Us

Since moving to Santa Fe, New Mexico in late 2018, I've been asked to what degree my new environment influences my work. It's a difficult question; on one hand, my approach to the work is constant and has never been overtly influenced by my surroundings. On the other hand, in recent years I have been more aware of the porousness of the studio walls; of course life experiences filter into the work in subtle ways—how could it be otherwise?

I tend to think through the sine qua non of painting the way that I imagine mathematicians, physicists, and astronomers think of the problems inherent in their respective fields; constants, rules, facts, and truths sit, cheek by jowl, alongside hypotheses, mysteries, and hunches. Constraints and parameters render the possibilities infinitely more tantalizing. Paintings share the facts of their making and reveal evidence of a succession of decisions, actions, and applications of one medium, color, or shape on top of another. In addition, paintings have the capacity to communicate thought, feeling and philosophy through a complex combination of association and suggestion. They also record succinct blocks of time; one starts a painting, and eventually finishes it, and it just might be possible that everything that is experienced adjacent and concurrent to the making of a painting somehow ends up in that painting, subtly embedded within its manifestation.

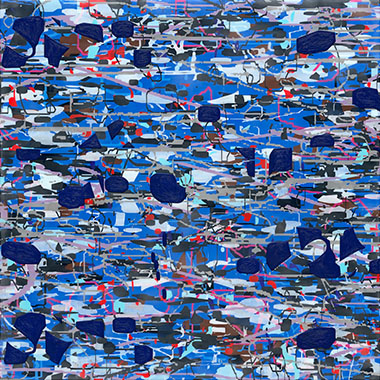

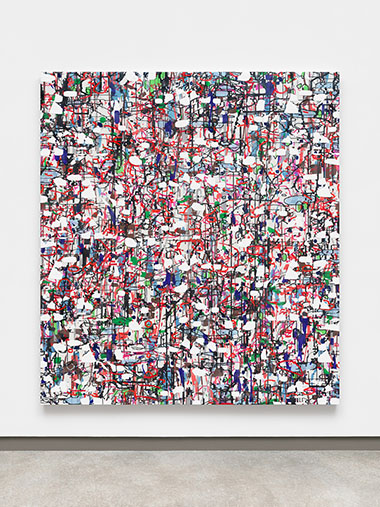

This body of work was made during a once-in-a-century pandemic that gripped our imaginations as much as it affected our day-to-day, physical, material existence. Within the hermetic and solitary process of making paintings, the dense thicket of my thoughts overwhelmed me at times. Hence, the daily practice of walking. I've walked well over a thousand miles since I began the work for this exhibition. Trail walking demands that the eyes stay on the ground for the most part, which suits me fine because, if I'm outdoors, I'm likely to be on the hunt for the perfect rock, potsherd, or fossil. Over the weeks and months of walking, I noticed that the landscape of Northern New Mexico is incredibly convoluted, thatched, and brambly. Everything is connected, layered, attached, intertwined, and interdependent. Most native plants seem inclined to grow down and sideways—not just skyward—as if to gain every advantage toward improving the chance of survival.

As I walked, I observed my surroundings and simultaneously obsessed over the goings-on in the studio. Inevitably, John Muir's words, "We are now in the mountains and they are in us . . ." cropped up and rang in my head like a mantra, repeating and repeating in a loop, until I'd look up from the trail to regard the various mountain ranges that cradle Santa Fe. Muir's evocative phrase suggests the anticipation of arrival as well as a recognition of our deep connection to the large masses of rock, soil, and vegetation that protrude, often in dramatic fashion, from the gentler contours of the earth.

A vast landscape ringed by mountains is an ideal arena for contemplation; the gaze is free to roam, yet is gently contained by an undulating boundary. Our local and storied mountains, always in sight, spurred thoughts of Cézanne and his many paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire. The idea of repeatedly representing an object or idea that is at once completely familiar yet ultimately ineffable; one that is concrete and tangible, but also full of symbolic meaning; one that is local and specific, yet also universal . . . well . . . as a painter, I understand his undying fascination with the mountain that was right out the back door, yet ever distant. Cézanne used the mountain as a template for deconstruction, for understanding, for precision in the expression of everything as a fragmented yet unified patchwork of cones, spheres, and cylinders, defining structure and spatial depth. I like to imagine that he also used the mountain as a stand-in for painting itself; the ever-shifting, elusive nature of it; its omnipresence; its mysteries.

Amy Ellingson's work has been exhibited nationally and in Tokyo, Japan. Her work is held in various public collections, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Crocker Art Museum, the San Jose Museum of Art, the Oakland Museum of California, the Berkeley Art Museum, and the U.S. Embassies in Algeria and Tunisia. She received a B.A. in Studio Art from Scripps College and an M.F.A. from CalArts, and was Associate Professor of Art at the San Francisco Art Institute from 2000-2011. Her 2015 public commission, Untitled (Large Variation), is an 1100 square foot ceramic mosaic mural, permanently on view in Terminal 3 at the San Francisco International Airport. She recently installed a large-scale commission for Sam Houston State University in Conroe, Texas, and has been awarded a commission for a new public work for the San Diego International Airport, which will be completed in 2024. A native of the San Francisco Bay Area, Amy Ellingson currently and works in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Photo credits: Eli Ridgway Gallery, Bozeman, Montana. John Janca, Artbot Photography