Migrations

It is not unusual for me to have doubts about my practice; to contemplate the relevance of and purpose for my art (making). Over these last few extraordinary months, the overlapping catastrophes of climate change, COVID-19, and the murder of George Floyd have inflamed my existential questionings.

In 2019, the world-wide teen-driven climate strike movement deeply moved me. At the time, I'd been trying to find my way into a new body of work. The iconic images and words of climate activist Greta Thunberg riveted me. I was mesmerized by photos of this humble, waif-like child, who through her super powers had captivated the world, and inspired the largest climate demonstration in human history. Using screen-captured video stills and photos as reference, I began making drawings of Greta. The pen and ink wash drawings were an opening that offered a way forward. Through the process of carefully observing her powerful child-like appearance, something began to emerge. The drawings, inspired by Greta, evolved into the series of paintings, Migrations.

Since 2010, I have painted on re-purposed domestic linens. The surfaces reference the history of women's handicrafts and allow for a more ecological art making practice. These fabrics, often hand stitched by the original owner, and aged with use, hold stories and histories, offering me clues of how to proceed. The Migrations paintings each depict a lone female nature figure who lumbers through flood waters, seeking refuge. In a large central panel, titled Offering, a chimeric creature has emerged on an island, where she kneels, making an offering before an animal-robot.

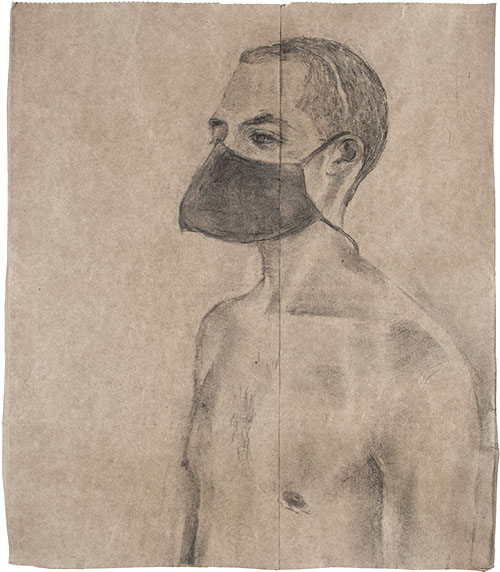

An exhibit of that work opened in February 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the U.S. Louisiana State University, where I am a painting and drawing professor, shut down. Thrust into the whirlwind of a global pandemic, the devastating news that my 82-year-old parents had tested positive for the coronavirus, and teaching art classes remotely, my studio practice came to a screeching halt. Miraculously, after many scary weeks, my parents recovered. When the spring semester finally ended, I was back in the studio, face to face with blank walls, and my demons. My 23-year-old adult child happened to be in the area just as the "stay at home" orders came. It has been a comfort to have them (they use non-gender pronouns) here during this challenging time. Since they were a toddler, Finn has often served as a muse for my work. So, with their blessing, I took advantage of the opportunity to use them again as a model. I began making drawings of Finn, using charcoal on Trader Joe's paper bags. The shopping bags were piling up, since we have been unable to use our reusable shopping bags during the pandemic. Drawing has always been a big part of my creative practice, but I hadn't made traditional charcoal drawings for many years. There has been something comforting about the directness of charcoal on the crumply brown paper.

The process has been meditative, and an anchor for me, during this trying time. Not long after beginning this work, George Floyd was murdered. It unexpectedly became unsettling for me to see Finn's white body drawn onto the brown surfaces, while I began to seriously educate myself to my white privilege. Gradually, the straightforward portraits of Finn, some depicted with and some without a (coronavirus) face mask, started to become more fantastical, his body merging with elements from nature. Each drawing depicts a solitary figure trudging through water, a refugee, seeking asylum.

Unwittingly, the Finn drawings have become part two of the Migrations body of work. Soon I will comb through the trunk of old linens, many gifted to me by people hoping to give new life to their family heirlooms. The dark, smudgy charcoal images will give way to color and painterly explorations. And I will find a sanctuary in the studio, my safe place for healing and refuge.

Kelli Scott Kelley is a Professor in the School of Art at Louisiana State University.