Conversations

For more than 30 years, my preferred art practice has been to create a series of works around a specific topic or theme. Although I hold degrees in both drawing and painting, I am a draftsman first and a painter second. I approach painting as one who draws with color.

Investigation and research are fundamental to my art. My dedication to visual detail springs from a desire to understand a thing deeply, including its scientific, historical and sacred aspects. My creative process is based on trying to make sense of the world around me and how I fit into this world. This continual investigation of topical social and cultural issues has engendered a new consideration of my role as an artist.

Clotilda, Clotilda Sacred, and Clotilda Transport Series

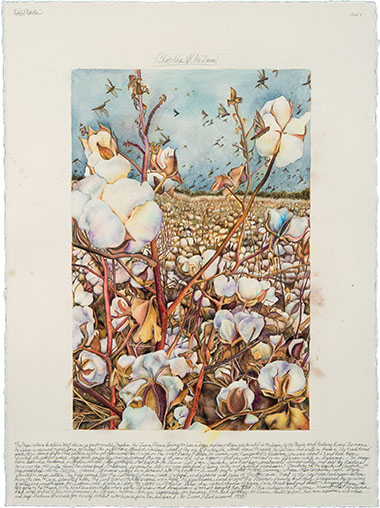

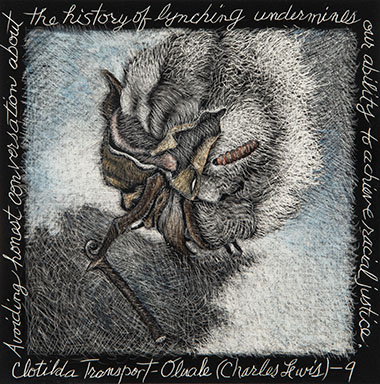

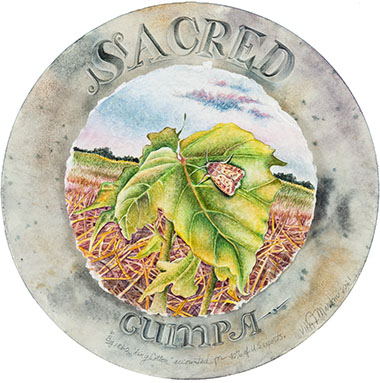

The art in this series uses the life cycle of the cotton plant to memorialize enslaved people and engage viewers in deeper conversations regarding racial peace and justice.

In 2018 and 2019, I traveled to the Deep South to learn more about the Civil Rights movement. These trips helped raise my awareness of the incredible story of the schooner Clotilda. On the eve of the Civil War, 52 years after the United States government had banned the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the Clotilda was the last ship to transport enslaved persons from Africa to the South. Running a Federal coastal blockade, the Clotilda docked in Mobile, Alabama on July 8, 1860, with a contraband cargo of 110 enslaved persons.

These 110 captives endured slavery for five years before being freed after the Civil War. Once emancipated, they sought to pool their money and return to Africa, but finding this impossible, they founded their own township just outside of Mobile. They called their community Africatown, and they sought to maintain their African customs and culture there. Africatown remains an active community today. Many of its residents are direct descendants of the original 110 persons brought to Mobile on the Clotilda.

When I began these works in February 2020, I had no idea that our world would be gripped by a global pandemic that would shine an ugly light on the racial disparities in health care in our country and in much of the world. Fifteen months later, George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police officers. A wound that had been festering for decades had finally burst, and we were forced to confront the blatant racial iniquities that blight our country and the world. I realized that my series about the survivors of the Clotilda transport was very timely and relevant.

The Clotilda Transport Series records the seasonal growth of cotton, and simultaneously memorializes several of the remarkable individuals who survived this last terrible middle passage on the Clotilda schooner from West Africa to Alabama. I hope this work encourages viewers to engage in frank and open conversation about our shared history so that we can better seek solutions to the issues of mass incarceration, racial disparity, and social injustice that continue to haunt our nation.

Descansos Series

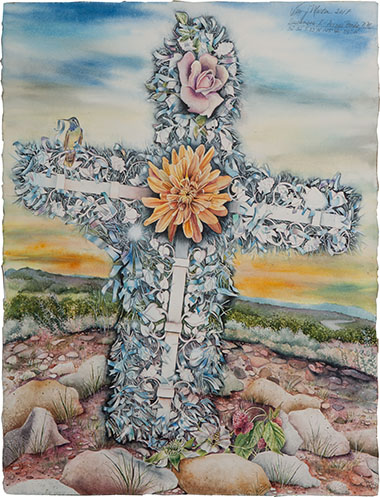

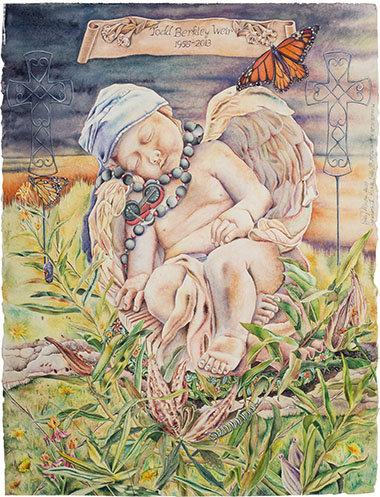

The Descansos Series is a suite of five watercolors that came about as the result of a road trip from Dallas to Taos in 2016 where I photographed roadside highway shrines along the way. In Spanish, descansar means "to rest." A descanso usually commemorates a site where a person died suddenly or unexpectedly away from home. It marks the last place on earth the person was alive.

I found the descansos I encountered fascinating. Every one was unique. Most incorporated personal objects of the deceased. As I left Texas and traveled into New Mexico, I noticed that as Hispanic culture became more predominant, the markers became larger and more elaborate. Many required creativity, skill, and time-intensive labor to construct. Some were heartbreakingly poignant, while others had almost a lighthearted, celebratory feel to them as they marked, according to their faith, the beginning of a loved one's transit to heaven. Some included the name of the deceased, while others were anonymous.

Documenting each descanso through photography and pinpointing its exact location using the GPS on my phone, I brought these sites to life when I returned to my studio in Dallas. I combined realism with surrealistic details and included the surrounding flora and fauna of the physical setting for each descanso. For some of the descansos, I was able to find obituaries or newspaper articles about the deceased, and this also informed those works.

Sacred Drawing Series

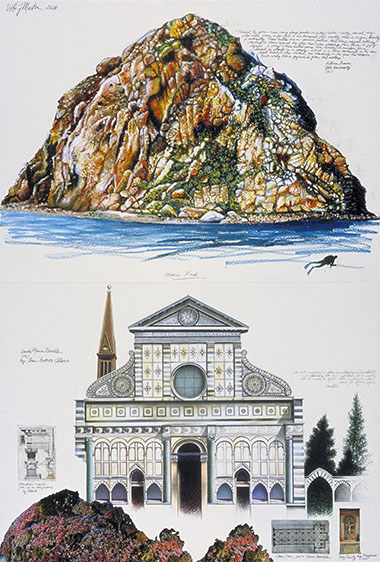

The Sacred Drawing Series is an exploration of dichotomous relationships, such as between the real and abstract, the profane and sacred, and the natural and man-made. These works employ a diptych format as a visual metaphor meant to suggest two facing pages in a giant sketchbook. One page in the diptych is devoted to an aspect of the dichotomous relationship. For example, one page treats the sacred, while the opposing page treats the profane. The works serve to illustrate my ongoing interest in the interconnectedness of objects, and my belief in an invisible and supportive framework behind the physical plane. I believe that this divine framework binds the universe together.

Sacred Drawing X compares the intricate architecture of Leon Battista Alberti's Renaissance masterpiece, the façade of Santa Maria Novella (1456-70) in Florence, to the geologic complexity of Morro Rock, a volcanic plug that forms a chain of nine similar peaks extending along the Pacific Coast from Morro Bay to San Luis Obispo in California. It is sometimes called the Gibraltar of the Pacific. In 1861, Professor William Brewster of Yale University described Morro Rock as "rising like a pyramid from the waters of the Pacific." This description is transcribed in the upper right corner of the piece.

Sacred Drawing XI is an exposition of pre-Columbian Mayan cosmology. One side of the drawing illustrates the Mayan creation myth as documented in the Popol Vuh, the sacred text of the Quiche Maya. After attempting to create a race of men from mud and wood who could worship them properly, the Mayan gods finally settled on creating man from maize. The Maya believed the earth's surface to be a great tortoise floating on a primordial sea. My image depicts the rebirth of the maize god in the form of teosinte, a grass that is the ancient ancestor of domesticated corn. On the left panel, a copy of the carved stone tablet from the Temple of the Foliated Cross at Palenque hovers above the cracked carapace of a turtle shell. Carved on the stone tablet is the World Tree, formed by a maize plant. In the crown of the plant sits the Celestial Bird and the branches of the tree are ears of maize manifested as human heads. This image symbolizes maize, which is not only the substance of human flesh, but also the major sustainer of life.

On the right panel, an image of corn is suspended above the ocean. Some of the written text on this panel is from a modern scientific document describing how corn pollinates. Other text, written in mirror writing, is a transcription of the Mayan creation story from the Popol Vuh.

Vikki J. Martin grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She received a BFA in painting from the University of Tulsa in 1976 and an MFA in drawing from the University of Texas in 1980. Most of her teaching career took place at the Episcopal School of Dallas where she taught Studio Art in middle school and Advanced Placement Art History to high school students, before retiring in 2017. She has shown her work regionally and nationally in galleries and museums including the San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts, San Angelo, Texas; the McCormick Gallery at Midland College, Midland, Texas; the Sarratt Gallery at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee; and Shidoni Gallery in Tesuque, New Mexico.